“Equality means more than passing laws. The struggle is really won in the hearts and minds of the community, where it really counts.”

—Barbara Gittings

Greetings, Defenders,

To those whose first time this might be at the tea table with us, and to those of you returning—welcome. I hope your week has gone well, or as well as any week can when you find yourself in the middle of the resistance in what can only be described as interesting times. Here, you will find safety, a listening ear, and the comforting shoulder of a friend—as well as the simple, unflinching truths they tell. In this space, we welcome all as they are, and welcome what you bring to the table, as you are able to bring it.

Today at the tea table marks a special moment. This is the midpoint of our Pride on the Page tribute series, which will find its final crescendo come Friday, July 4th. So far, we have honored resistance in its many forms—loud and quiet, flamboyant and fierce—and celebrated those who fought not only for themselves, but for all of us. But today, we arrive at the very heart of why this series exists.

Because knowledge is power.

It is how we come to understand ourselves. It shapes the world we inhabit. It arms us with the tools to think critically, to question what we are told, and to rewrite what we’ve been taught. And there is perhaps no one who knew this more intimately—who fought so fiercely to restore the truth—than Barbara Gittings.

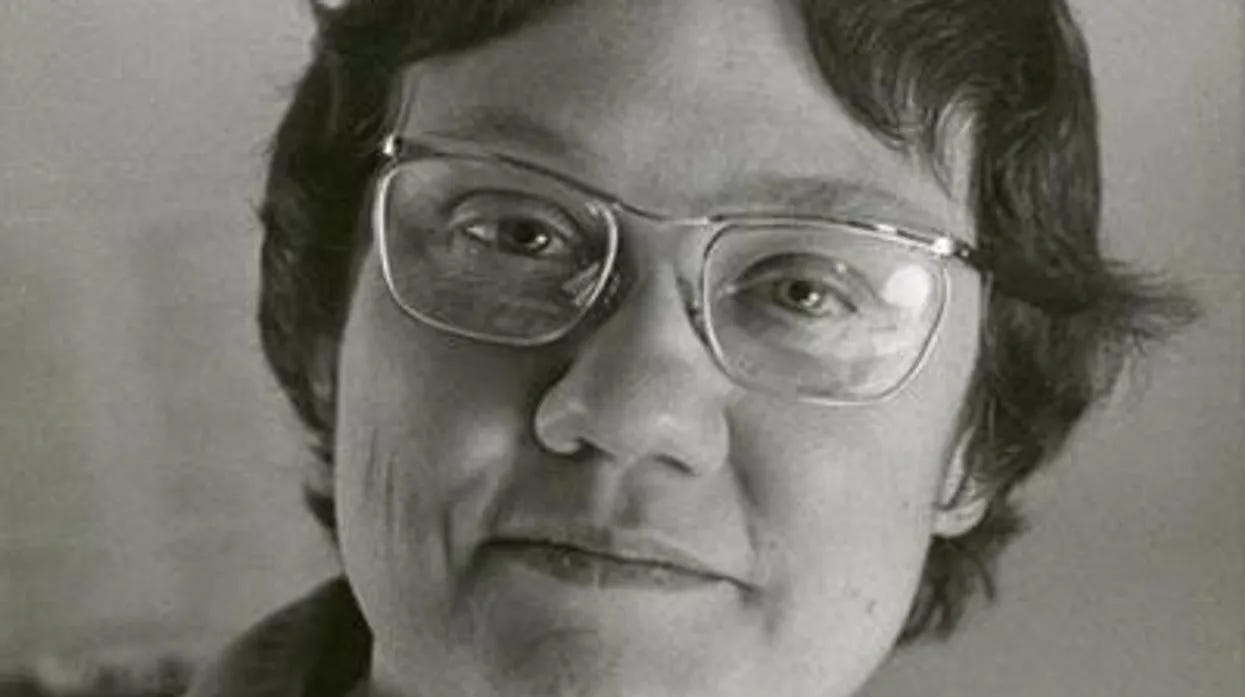

A woman of poise, purpose, and extraordinary precision, Barbara wasn’t interested in screaming into the void. She was interested in making sure you could find yourself on the shelf. In making sure your life could be studied—not stigmatized.

She taught us that the war on queer lives was being fought not just with laws, but with language. And she was more than ready to fight back.

A Girl With a Question

Barbara Gittings was born in 1932 to a family stationed overseas—her father a U.S. diplomat, her upbringing shaped by international exposure and a deeply Catholic education. She attended an all-girls Catholic high school, where she quickly learned how little space the world made for people like her.

Barbara knew early that she was different. She felt an unmistakable pull toward other girls, but had no language to define what it meant. There were no books, no conversations, no names—only silence and shame. It wasn’t until a teacher at her high school informed her, with a certain cruel clarity, that she had “homosexual tendencies” and was therefore ineligible for the National Honor Society, that the pieces began to click. She was being named before she had even found the words for herself.

Still determined, she enrolled at Northwestern University. There, she formed a close bond with another female student—and found herself, for the first time, falling in love. That revelation terrified her. Without knowledge or support, she did what many in her time believed they must: she sought help from a psychiatrist.

That doctor did not offer understanding, but rather a “cure.” A supposed treatment for what was, by official classification, a sickness. Yet it was this attempt to be cured that catalyzed something far more powerful in Barbara: a hunger for truth. She began to read. She began to search. She poured through any text she could find, from medical journals to psychology books to what little literature existed about homosexuality—most of it clinical, hostile, or pathologizing, but still, it was something. Still, it was knowledge.

That pursuit became her quiet revolution.

The deeper she read, the more questions she asked—and the fewer answers the world had. Unable to concentrate on her coursework and overwhelmed by the emotional toll of her identity crisis, Barbara failed out of Northwestern. She returned home in defeat, carrying not just books but something far heavier: the still-forming truth of who she was.While she would come home carrying the secret of why she had failed out, that secret would not be her for long. Her father discovered the reading material she’d been gathering in secret and confronted her. In that moment, she came out to her family—her truth, no longer deniable or deferred.

At just 18 years old, she left home and moved to Philadelphia to start anew. That departure wasn’t just geographic. It marked the beginning of a lifelong journey: the pursuit of knowledge, the reclamation of language, and the opening of doors that had long been shut—for herself, and for every soul who would one day walk through them.

From Stigma to Strategy

For years, Barbara searched in vain for truth, only to find herself sifting through scraps. Much of what was written about homosexuality in the 1950s was cold, clinical, or cruel—written by those on the outside looking in, and looking down. Yet like so many who were desperate to understand themselves, Barbara clung to even the worst of it. When no doors are open, even a crack in the wall feels like a window.

That hunger for clarity eventually led her to the Daughters of Bilitis—the first lesbian civil and political rights organization in the United States. Though she lived in Philadelphia at the time, she was asked to establish and lead a new chapter in New York City. And so she did, becoming president of the New York DOB chapter and editor of their modest newsletter. For three years, she helped shepherd the group through a fragile moment in LGBTQ+ organizing, where safety was precarious and truth was elusive.

Within the DOB meetings, Barbara encountered a painful paradox: even in these supposed safe spaces, lesbians were still subjected to lectures by so-called experts who pathologized them—doctors who spoke of homosexuality as a defect or disorder. The women gathered listened anyway, because scraps were still scraps, and scraps were still more than nothing. But Barbara began to imagine something better.

By 1963, she joined The Ladder—the DOB’s national publication—as editor, a role she would hold until 1966. And that is when the tone began to change. Under Barbara’s stewardship, The Ladder began to shift from survival to strategy. She featured real lesbian voices and stories, showcasing the lived realities of women who refused to be defined by pathology. She curated articles not merely by availability, but by value: accuracy, accessibility, and affirmation became the new criteria. Where once the bar had been “at least it mentions us,” Barbara raised it to: Does it tell the truth about us?

It was here that Barbara Gittings stepped fully into her power. She had consumed the knowledge. She had tested it against her own life. And now, she wielded it with purpose.

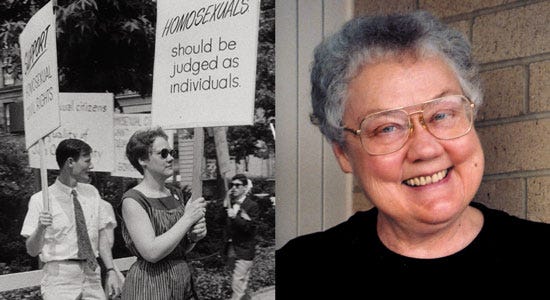

By the mid-60s, she was marching with other activists including Frank Kameny, joining the earliest organized LGBTQ+ protests in the country. On July 4, year after year, they picketed the White House and Independence Hall with carefully dressed resolve, demanding recognition and equality. These protests would help lay the emotional and political groundwork for what would soon rise at Stonewall.

And Barbara didn’t stop there.

In 1967, she partnered with Frank Kameny again to challenge one of the most pernicious lies of the era: that homosexuality could be “cured.” Charles Socarides, a prominent psychiatrist, was preparing to testify before the Department of Defense, advocating for this twisted pseudoscience. Barbara and Frank worked tirelessly behind the scenes to discredit his testimony and ensure the truth was heard. And they succeeded. The Department rejected Socarides’ claims. A cruel chapter was stymied—though tragically, its shadow still lingers in the practice of conversion therapy, promoted by the far-right to this very day.

Through the final years of the 1960s, Barbara was unstoppable. She gave hundreds of public lectures, appeared in debates, and kept a foot in every possible door—each speech a strike against the classification of LGBTQ+ identity as illness. She did not merely ask the world to see queer people differently; she demanded it. Her very life became the counterpoint to their diagnosis.

And yet, for Barbara Gittings, speaking out was only part of the work. It was just one battlefield in the larger war. If the heart of the fight was misclassification—then the library stacks, and the systems behind them, would be her next front.

Information as Liberation

Barbara Gittings spent the 1970s wielding truth like a lantern, illuminating institutions that had long preferred shadows. Her battlefield was not just the protest line—it was the bookshelf, the broadcast, the podium, and the printed word.

She began the decade by founding the American Library Association’s first Gay Task Force in 1970, recognizing that access to honest, affirming information was not ancillary to justice—it was justice. At a time when most books on homosexuality were either clinical diagnoses or cautionary tales, she worked to curate and catalog a new canon—one that celebrated queer existence rather than diagnosing it. And she saw the gaps that others missed: the need for age-appropriate material, for children who might stumble into these feelings and be told not that they were ill, but that they were extraordinary in their own way.

What others dismissed as mundane—card catalogs, subject headings, bibliographies—she understood as battlegrounds. Lifelines. She knew that a single book could dismantle shame, that the ability to see yourself on a library shelf might make the difference between silence and survival.

But Gittings didn’t stop at libraries.

In 1972, she helped organize what would become a historic intervention into the American Psychiatric Association. At the APA’s annual meeting, she helped orchestrate a panel featuring a masked psychiatrist—Dr. John Fryer—whose disguised voice condemned the profession’s labeling of homosexuality as a mental disorder. Dr. Fryer had only agreed to appear under these conditions, for fear his medical license would be revoked. She would also read letters from other doctors who had felt too afraid to show up. She knew the risk. But she also knew the cost of silence.

That moment, broadcast through the halls of medicine, helped lead to the APA’s landmark 1973 decision to declassify homosexuality as a mental illness. And Gittings kept returning, year after year, until the last echo of shame was gone. Her final APA presentation in 1978 bore a triumphant title: “Gay Love: Good Medicine.”

During this same span, Barbara Gittings became one of the first openly lesbian women ever televised in the United States. In an era when queerness was either a slur or a secret, she stood visibly, calmly, and joyfully in front of the camera. Not to shock. Not to defend. Simply to exist. To show the world what dignity looked like.

She never underestimated the power of visibility. She knew that truth did not trickle down—it had to be carried, hand to hand, heart to heart, book to reader, image to screen. She carried it, tirelessly.

The Work Endures

Barbara Gittings did not retire from the fight—she simply changed its form.

In the 1980s and beyond, she remained an unrelenting presence in the movement, working not just to protest what was wrong, but to preserve what was right. She understood that history, too, could be a battleground. So she began archiving, curating, and organizing the movement’s memory. Alongside her life partner, photojournalist Kay Lahusen, Gittings began assembling the documentation that would later form the backbone of our understanding of early queer resistance.

She spoke on panels, mentored new activists, and remained deeply involved in the American Library Association. She pushed for broader inclusion in medical and educational spaces, insisting that the next generation should never be forced to unlearn shame before learning pride.

Even as AIDS ravaged the community she loved, even as political backlash threatened hard-won gains, Barbara Gittings held the line. Not as a celebrity. Not as a figurehead. But as a stubborn optimist who knew that love—when paired with knowledge—was revolutionary.

She died in 2007, in the city where so much of her work had bloomed. She left behind no biological children, but thousands of spiritual heirs—librarians, lovers, leaders—who walk through doors she forced open.

The Shelf Still Speaks

Today, her legacy whispers from places you may not expect: the rainbow sticker on a library door. A child quietly pulling a book from the “LGBTQ+” shelf. A classification system that no longer sorts human beings under pathology.

The Free Library of Philadelphia bears her name, as does an American Library Association award for lifetime service. She is honored not in bronze, but in access—through every book that tells a young person they are not alone, not broken, not wrong.

She taught us that visibility is not vanity. It is survival.

She showed us that shame is not an identity—it is a weapon, one that can be disarmed through words, pages, panels, and presence.

And she left us a question wrapped in a challenge: now that we have found the truth—what will we do with it?

“It’s not enough to counter lies and myths. We must affirm who we are. We must teach people the truth about our lives.”

—Barbara Gittings

Barbara Gittings knew the stakes. She knew that injustice did not thrive on hatred alone—it fed on ignorance, on silence, on the absence of our stories. And so she made it her life’s work to ensure those stories could be found, not hidden. Shelved with care, not shame. Spoken with pride, not apology.

This is her lesson. The lesson of the new phoenix, summoned once more in this aviary of firebirds:

Knowledge is truth.

Knowledge is power.

And if we allow our stories to be written by those who know nothing—but pretend to know everything—then we will always be the villains. Or worse, the forgotten.

That is why we write these tributes.

That is why we remember.

That is why we walk into the ashes—not to mourn, but to tend the fire. To care for the phoenixes who rise once more, bearing names like Gittings.

Until our next bold move,

~ Lady LiberTea ✨🫖

Tending the Flame, Carrying the Truth

Barbara Gittings reminded us that a single book, a single voice, a single truth can change everything. Her shelves saved lives. Her voice unmasked injustice. Her work lit torches in the darkness.

📚 Defend LGBTQ+ Books in Schools & Libraries

Donate or request affirming K–12 titles through GLSEN’s Rainbow Library, which has sent LGBTQ‑inclusive books to over 1,700 schools

Support Pride & Less Prejudice, a Wisconsin nonprofit sending LGBTQ books into classrooms and pushing back against bans

Purchase from or donate to Fabulosa Books’ “Books Not Bans” campaign, sending queer books to communities facing censorship

🗳️ Step Up: Run or Elect LGBTQ+ Voices to School Boards

Endorse or volunteer with LGBTQ Victory Fund, which backs out LGBTQ+ candidates—like many running for the first time on school boards.

Learn best practices for LGBTQ+ representation on school boards via School Board Partners, including drafting inclusive policies

Join the national wave: in recent years, 80+ openly LGBTQ+ individuals have run for local school board seats—more than double the 2020 count .

🧭 Support LGBTQ+ Youth

Donate or volunteer with The Trevor Project, the largest crisis helpline and mental health resource for LGBTQ youth. During Pride, matching contributors are donating 3 dollars for every dollar raised,

Empower education and leadership among young LGBTQ+ people through GLSEN, PFLAG, Human Rights Campaign, and local organizations in your area—find chapters at their websites

Find a library, nominate yourself or someone you know for office, donate a book, volunteer an hour—or even run for school board yourself.

Each step feeds the next spark. Each story carried into classrooms, council meetings, or living rooms nourishes another phoenix rising.

Because phoenixes don’t rise by accident.

They rise because someone—someone like you—tended the flame.

Keep tending, my dear defenders,

~ Lady LiberTea ✨🫖

Wow—thank you for the deep level of research!

Gittings is a revered saint in the queer library world—a discipline I come from! I’m an ex-public librarian and worked in both archives & libraries.

It’s not an easy path to get a bachelor’s then the MLIS degree is a lot of research and writing—but also learning about systems of organization and how people find it, manage it and disseminate it.

So, I’m always interested (and amazed) by how lay people access information, synthesize it as you’ve done, then write a fantastic article! Great job! ♥️✨

This is fabulous writing, as usual. I am old enough to recall a time when representation and community were hard to find outside the bars. I was so grateful for the lesbian writers out there for telling their stories. They made me feel seen and gave me words to understand myself. I couldn't wait to make my weekly trek to Thackery's Book Store to peruse their lesbian section for my selections that week. Thank you for bringing that back to me by telling Barbara's story.